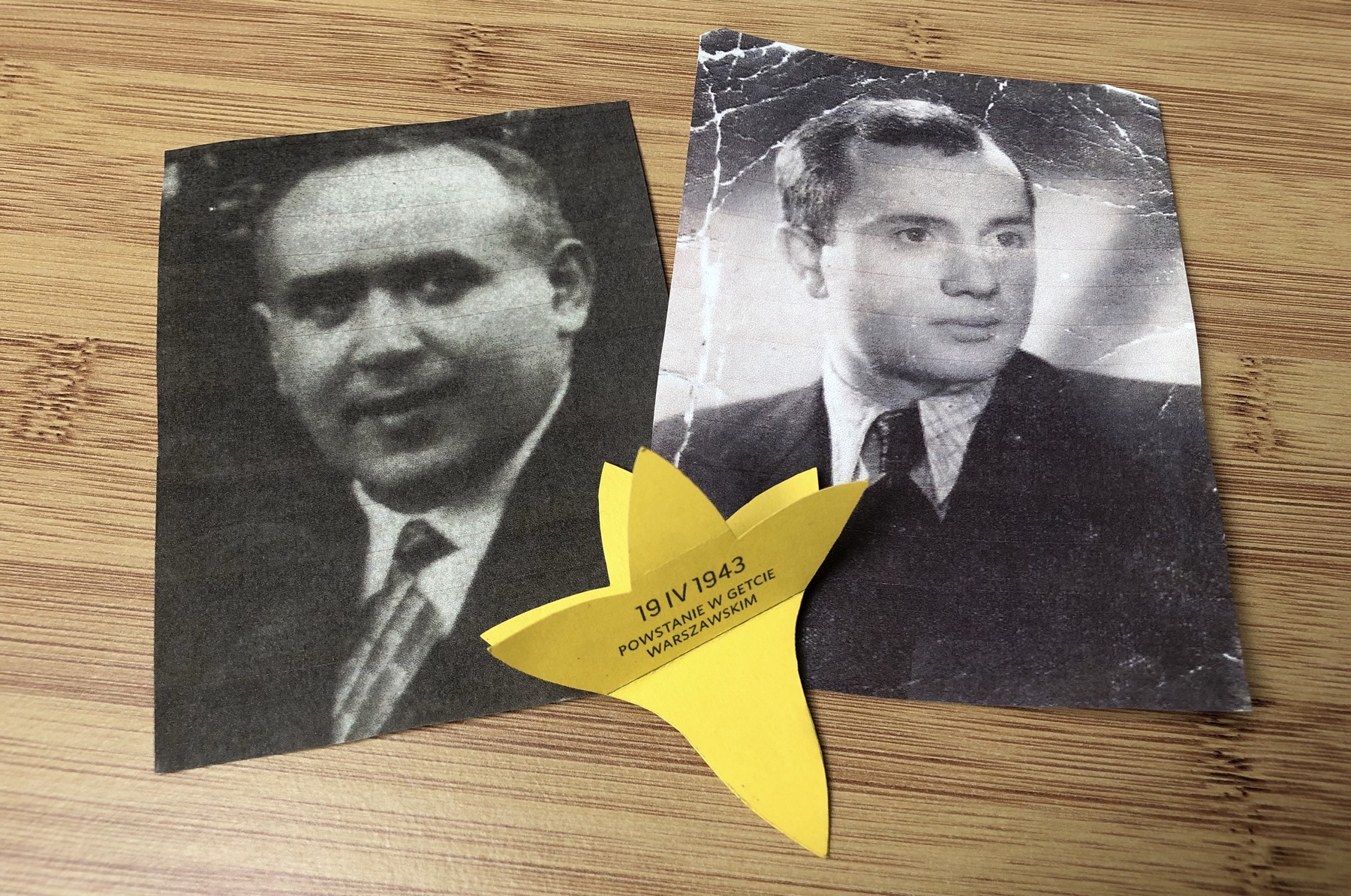

Kazimierz Mayzner was born on July 6, 1883 in Warsaw, as the son of Izydor and Anna née Woldenberg. His father was considered a humanist and a patriot, he was an outstanding industrialist, co-owner of a trade company, co-founder of the Mayzner Society of Sugar Factories and sugar factory administrator, member of the Technicians Association in Warsaw and the Public Library Society in Warsaw, founder of schools, shelters and reading rooms. The Woldenberg family was, in turn, one of the more popular and distinguished Jewish families in Płock. Dawid Woldenberg, owner of the property at the former Kanoniczny Square, at Teatralna Street and the property of Nagórki Dobrskie, Wierzbówiec and the palace in Luberadz, was a well-known Płock philanthropist, co-founder of the Town Credit Society and Płock Charity Society. For many years he was also a member of the Volunteer Fire Brigade and a member of the Synagogue Supervision Board.

In 1903, Kazimierz Mayzner graduated from the 5th Government Philological Gymnasium (Middle School) in Warsaw, the graduates of which were, among others, Leo Belmont, Józef Hersz Dawidsohn and Marceli Handelsman. He also studied at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology, then left for Paris, where he also studied painting. In 1911 he graduated in law from Dorpat. In the years 1911–1917 he served as an assistant to lawyer Karol Gustaw Dunin, then as a counselor of the Central Welfare Council. In 1917, Kazimierz Mayzner came to his mother’s hometown, where he took the position of a deputy prosecutor, later a prosecutor, at the District Court in Płock. At that time, he lived in a tenement house at 6 Dobrzyńska Street (currently Kazimierza Wielkiego). In 1918 he joined the Town Council in Płock. During the Polish-Bolshevik war, he volunteered to join the army, where he served for two years as a lieutenant – auditor of the judicial corps.

In 1921 he was entered on the list of lawyers of the Law Council in Warsaw, department of Płock. Although, as Kazimierz Askanas recalls, law was a passion for Kazimierz Mayzner, he also was an activist in various areas of politics: he was associated with the Polish Socialist Party, then the National Workers’ Party and Christian Democracy. At the same time, he was the author of numerous articles published in newspapers and magazines (“Gazeta Polska”, “Scena Polska”, “Życie Mazowsza” and “Dziennik Płocki”), editor of “Przegląd Płocki” and “Głos Płocki”. He was one of the active members of the Tourism Support Association established in 1935 in Płock, whose goal was to promote tourism to Płock and its organization.

The greatest work of Kazimierz Mayzner’s life was the Artistic Club of Płock.

In 1929, with the participation of a small group of artists, musicians, writers as well as experts and art lovers, he set off to promote artistic life in Płock and create an art club in the town. The club was initially called the Płock Artists’ Club, from 1931 – the Płocczan Art Club (in Płock it was known as KAP). Thanks to the efforts of Kazimierz Mayzner, KAP became a user of the Płock theater building with a large exhibition hall and a modernly furnished café with a large garden and dancing space. The Artistic Club of Płock conducted broad activity, becoming the main organizer of cultural life in Płock: it organized exhibitions, lectures, discussions, performances and concerts. At exhibitions, the club presented works of, among others Natan Korzeń, Fiszel Zylberberg, Erna Gutkind, Maksymilian Eljowicz and Abraham Skórnik. Kazimierz Mayzner supported artists, painters and musicians by helping them with selling paintings and in organization of concerts.

As Kazimierz Askanas points out: “KAP’s activities created the town’s cultural and artistic atmosphere, not present there before, encouraging an unusual revival of cultural life, and in particular, creative work. The creation of the Artistic Club of Płock and Kazimierz Mayzner, who was the creator and main activist of this institution, should be considered a unicum on a national scale […] He managed to introduce the Club on the path of broad popularization of culture. At the same time, he expanded the Club’s activities to take care of artistic craftsmanship, and finally – the town’s aesthetics”.

Kazimierz Mayzner’s great success was “Szopki Płockie” (“Płock Farces”) – unusually accurate satires on representatives of the authorities and intelligentsia of Płock and the ideology of BBWR, as well as the exhibition of his play “Dziewczyna z winiarni” (“The Girl from the Winery”), which enjoyed great popularity among the inhabitants of Płock. Kazimierz Mayzner was awarded the laurel of the Polish Academy of Literature and the Gold Cross of Merit.

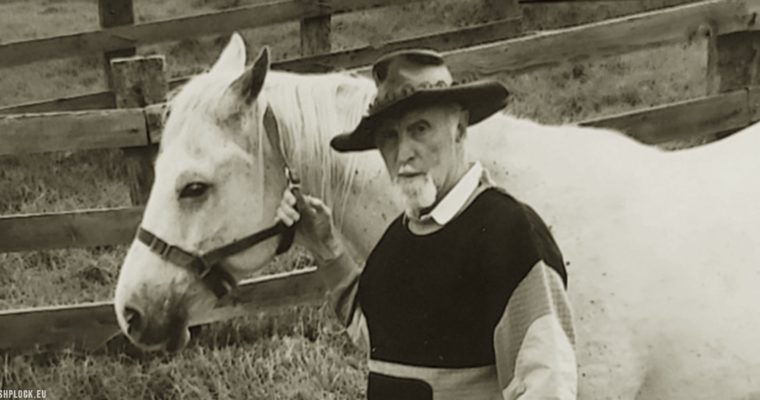

The activity of the Art Club of Płock was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. Kazimierz Mayzner volunteered for the 4th Cavalry Regiment. After the war, he was imprisoned in the Murnau camp. After being released from the camp, he came back to Płock and returned to his legal practice. He died on March 28, 1951.

Bibliography:

Askanas K., Adwokat Kazimierz Mayzner – znana postać na Mazowszu, „Palestra” 30/7(343), 1986, pp. 53-59

Askanas K., Sztuka Płocka, Płock 1991

Przedpełski J., Stefański J., Żydzi płoccy w dziejach miasta, Płock 2012