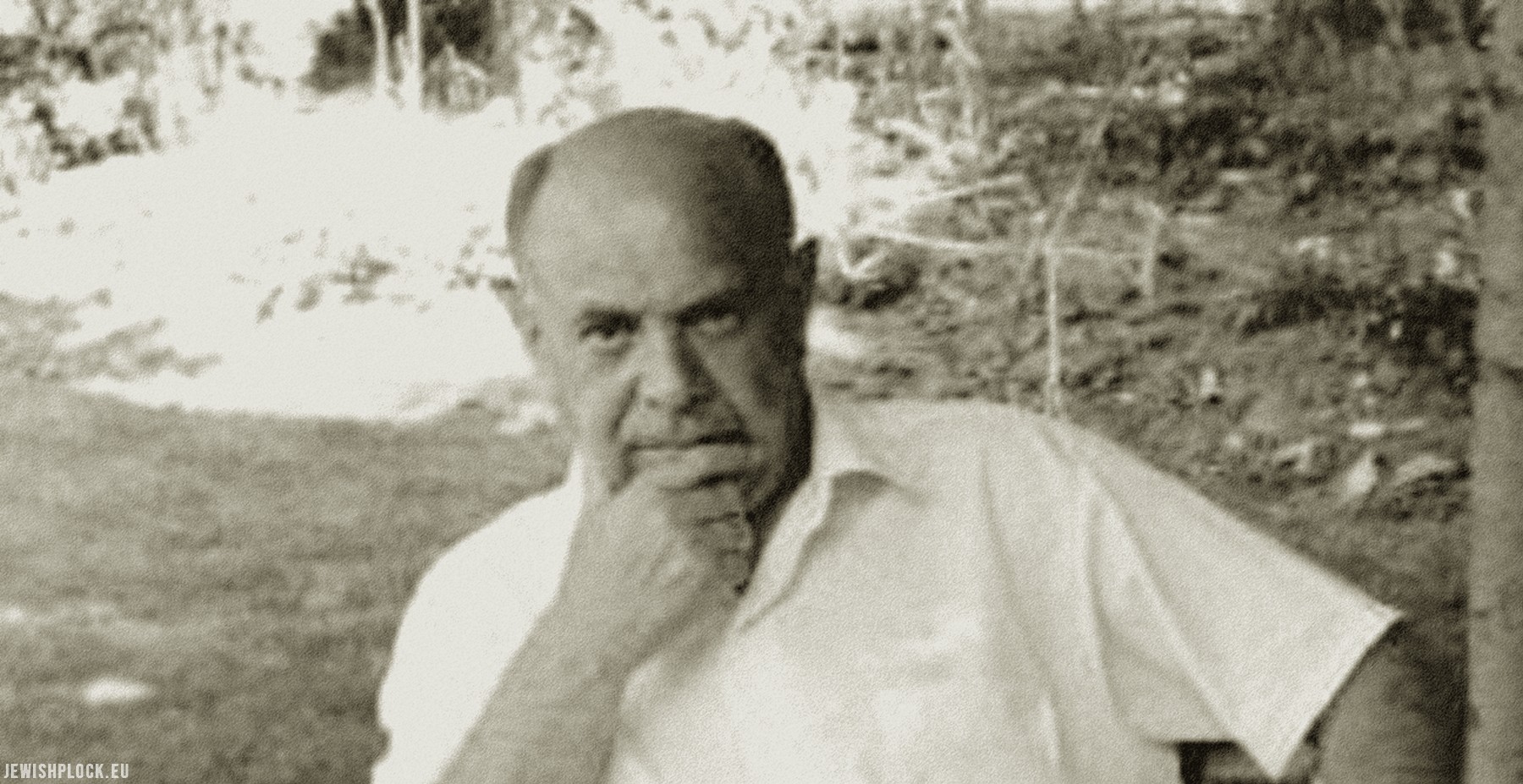

Dr Roman (Rywen) Pakuła was the son of Mojżesz Aron and Enta, his family lived at 4 Grodzka Street in Płock. Below we publish two texts devoted to this extraordinary citizen of Płock and a valued scientist.

Doctor Roman Pakuła – a biographical sketch prepared by his colleagues at the Department of Microbiology at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Roman Pakuła was associated with the Department of Microbiology of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto between July 1966 and June 1982. He was born in Płock, Poland on January 10, 1910 and died in Toronto on September 19, 1986. He is survived by his wife Zofia, a retired physician, and by his son Andrew, a management and applied social research consultant.

During 1931-1937, with the assistance of scholarships for gifted students, Roman began his life-long career as a biological scientist at the University of Warsaw. He elected to specialize in microbiology, a choice which kept him at the forefront of biological and medical research throughout his lifetime. He was awarded his Master of Philosophy degree in 1937. His research thesis was entitled “Morphology and physiology of two strains of Azotobacter vinelandii. Nitrogen fixation and saccharose uptake”.

Roman began his doctoral studies in 1937. Following the September 1, 1939 German invasion of Poland, which launched World War II, he fled to the western region of the Soviet Union, where he continued his Ph. D. studies at the University of Cazimir in Lwow. In 1941, when the U.S.S.R. was invaded by the Germans, Roman was drafted into the Russian army. He fought with them throughout the war and participated in the decisive battle of Stalingrad, now known as Volgograd. For one year after the war, Roman remained in Stalingrad as a lecturer in the Medical School.

In 1946 Roman returned to Warsaw to Zofia Graubart (the biogram of Zofia Graubart Pakuła can be found here – link), whom he had married in January of 1940. He resumed his interrupted Ph.D. studies and at the same time taught biology and chemistry during 1946-1948. He defended his Ph.D. thesis entitled “Extraction of the T antigen from Streptococcus pyogenes” in June of 1950. In 1953 he earned the degree of Dozent in Science through the Medical School at the University of Warsaw. The title of his thesis was “The polysaccharides of hemolytic Streptococci. Analysis by precipitation and agglutination methods”.

In 1954 Dr. Pakula began his professorial career when he received the title of Professor at the University of Warsaw. Between 1953 and 1964 he was Head of the Department of Microbiology at the Medical School where he taught Bacterial Genetics. In 1948 he had been named Director of the Streptococcal and Staphylococcal Reference Laboratories at the State Institute of Hygiene, a post which he retained until he left Poland.

The esteem in which Dr. Pakula was held by his colleagues, and his outstanding contributions to microbiology, bacteriology, serology and the molecular biology which was beginning to emerge, was attested by his appointment to the Polish Academy of Science. He was Secretary of its Microbiological Committee between 1953 and 1964. During 1962-1964, Dr. Pakula was Head of the newly established Laboratory of Bacterial Genetics of the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. In 1949-1950 he was a Fellow of the World Health Organization and worked at the Central Public Health Laboratories at Colindale in the north of London, England. Dr. Pakula’s international reputation was by now assured and between 1949 and 1964 he visited many research institutions throughout the world to describe his revolutionary research in genetic transformation of bacteria. Because of his expertise, he was appointed to the International Subcommittee for Phage Typing of Staphylococci and to the International Subcommittee for Streptococci and Pneumococci.

The summer of 1962 was a germinal one for Dr. Pakula and the University of Toronto. He attended the International Congress of Genetics in Montreal where he was approached by the Director of the Connaught Medical Research Laboratories (CMRL) about the possibility of his coming to that institution. And indeed, in 1964 Dr. Pakula was officially invited by Dr. J. K. W. Ferguson to come to CMRL as a Visiting Fellow. This he did and remained as a Research Associate at their Dufferin Division between March, 1964 and June, 1966, at which time he was named Associate Professor of the Department of Microbiology, then at the School of Hygiene at the University of Toronto. On July 1, 1967 Dr. Pakula became a Full Professor and five years later was named Acting Department Chair. He retained that post until his retirement in July 1, 1975, then continued to teach graduate courses on a part-time basis for seven years.

Dr. Pakula had a wonderful sense of humour and a zest for life which made him a brilliant raconteur and therefore an outstanding teacher at the podium and at the laboratory bench. His love and respect for human beings shone forth at every turn. Without even trying, he transmitted to his colleagues the ever-present curiosity, joy and excitement in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding, which are the hallmarks of a great scientist and a great humanitarian. Throughout his career he lectured to students of fundamental science, medicine, nursing and pharmacy. Dr. Pakula’s most enduring legacy to the university was his elevation of the Department of Microbiology to one which was fully engaged in all the activities of an academic science-based department, which also was to have an impact on medicine and health in all subdisciplines of microbiology. He placed special emphasis on the intellectual endeavors of science and the requirements of professorial teachers to inspire and encourage the development of the next generation of Canadian scientists. Thus he devoted considerable efforts to the supervision of graduate students.

To do him honour, Dr. Pakula’s family and his colleagues established the DR. Roman Pakula Award given annually to the best M.Sc. student in the Department of Medical Genetics and Microbiology at the University of Toronto.

Presentation by Andrew Pakula, Roman Pakula Award, Microbiology Department, March 29, 1996

Because of the time and place of his birth, my father’s life was profoundly effected by powerful and destructive forces of history – war, hatred, racism, fascism and communism. His survival and even more so his success as a scientist were very much against the odds. After his graduate studies were interrupted by World War II, he became a soldier in the army that defeated the Nazis under conditions of unimaginable hardship.

In Poland and in other communist countries after the war, the sciences, particularly the biological sciences, were corrupted by the mad ravings of Stalin and his henchmen trying to subvert truth in the name of totalitarian ideology. The Lamarckian ideas about the inheritance of acquired characteristics, expressed by Lysenko and others of his ilk, were the enforced “truth”. My father, unconcerned about the risks, spoke up against such nonsense and supported fellow scientists who were victimized by the regime. He believed that science without utmost integrity was not worth much.

He took enormous pleasure in his work as a teacher and a researcher. I recall going to his lab as a child and being struck by the sheer joy showing on his face. He was fond of saying – “I am so lucky to be getting paid for my hobby”. Although he was a hard taskmaster, his students liked and admired him for his knowledge, his abilities as a teacher and a story teller, and his great sense of humour. I am very grateful to him for teaching me to be curious about the world. More than anything, he was a scientist. He admired and aspired to excellence and so he would have been very proud to be associated with this award.

Texts (originally published on zchor.org) and photos courtesy of Andrew Pakuła.