The oldest mention of the Sadzawka family in Płock dates back to 1810 – on June 22, in the Płock Notarial Office, a purchase contract was concluded for the sale of part of the property located at Synagogalna Street (mortgage number 39) between Józef Markus Pozner and Józef Sadzawka (Józef Mośkowicz at the time). Józef Mośkowicz also purchased the second part of the property under a contract of November 24, 1814 from Anszel Rotman.

Józef Sadzawka (1782-1838) was a trader, and archival sources also record him as one of the Jews from Płock who ran a private house of prayer in the town.

In 1824 Józef Sadzawka purchased a property at Bielska Street, mortgage number 243B. The multi-generational Sadzawka family lived on Bielska Street until the outbreak of World War II.

The first wife of Józef was Sura, with whom he had a son Szaja Zajnwel, his second wife – Bajla née Szymek. Józef Sadzawka was also the father of Wolf, Abraham, Lejbusz, Itta, Dyna and Ryfka.

Szaja Zajnwel, a translator by profession, was married to Gitla (1828-1900), daughter of Kazriel and Bajla Granat. Their eldest son Józef was born in 1856. In the following years, Tyszla Małka (born in 1858), Emanuel (born in 1860) and Moszek Aron (born in 1864) were born as well.

The wife of Emanuel Sadzawka was Małka née Askanas, daughter of Jakub Szulim and Maria Perelgryc, born in 1855 in Płock. Their children were Łaja (born in 1888) and Jakub Szmul (born in 1889). As part of his everyday job, Emanuel Sadzawka sold carbonated drinks in a booth at Konstantynowski Square.

Moszek Aron Sadzawka married Ryfka Wajcman from Wyszogród, daughter of Jochim Wajcman and Estera Sura née Albert. The children of Ryfka and Moszek Aron were: Samuel (born in 1896), Bajla (born in 1897), Dyna (born in 1898), Małka (born in 1899), Szaja (born in 1901), Kasryel (born in 1903) and Gitla (born in 1907). From the beginning of the 1880s, Moszek Aron Sadzawka dealt in the trade of tobacco products in Płock. In the interwar period he ran a furniture sales company.

Since 1860, the owner of the property at Bielska Street was Gitla Sadzawka. She bought the property from Abram Jagoda, who bought it in a public sale, after division of the inherited property by the heirs of Józef and Bajla. After Gitla’s death in 1908, her children became owners: Moszek Aron, Emanuel, Józef and Tyszla Małka. In the same year Moszek took over the parts belonging to his siblings and became the sole owner of the property until his death in 1936. The last owner of the property before the war was Abram Sadzawka.

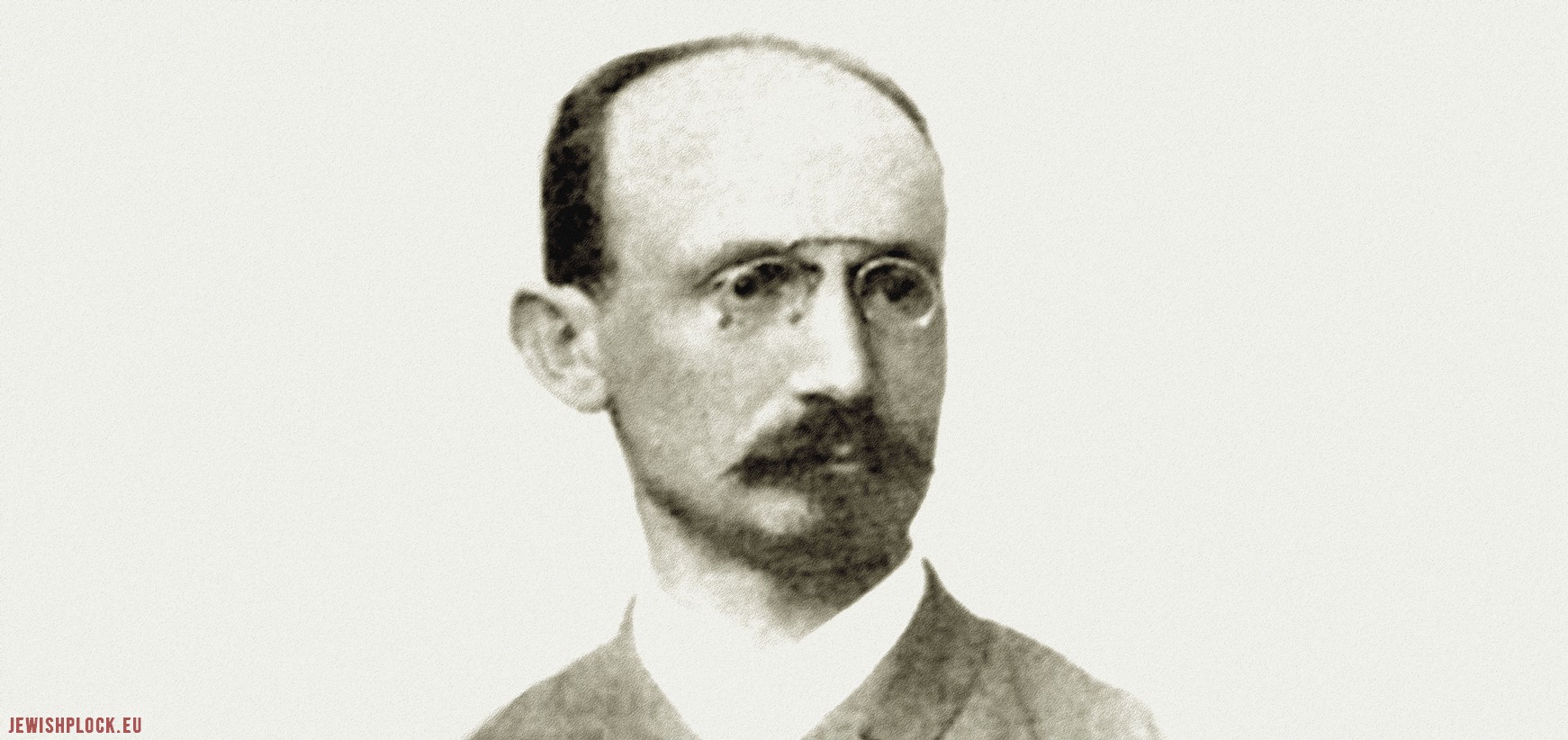

Before 1882, Józef Sadzawka, son of Szaja Zajnwel and Gitla, emigrated to Belgium. At the age of 26, he married Maria Ungermann (born in 1859) from Dahleram (Germany), daughter of Mathias and Julianne Matheÿ. Józef and Maria had four children: Emil (born in 1882), Julia (born in 1884), Jeanne (born in 1888) and Ernest Leon (born in 1890). The Sadzawka family lived in the north-west district of Brussels – Laeken.

Józef Sadzawka made a stunning career in the tobacco industry in Brussels. Before 1888, he founded the well-known manufacture of cigarettes and Turkish tobacco (Manufacture de Cigarettes & Tabacs Turcs J. Sadzawka), located at rue Linnée 62, then at Avenue de la Reine 286. His successes in this field can be proved by the Grand Prix, which he obtained during the world exhibition in Brussels in 1897. Later, he presented his company and products at the world exhibition in Liege in 1905.

The tobacco industry was then a relatively young industry. The first cigar factories were established in Antwerp and Ghent between 1840 and 1850. Then the industry spread to other cities, and Belgian factories quickly became known throughout the world. Cigarette manufacturing began even later. Józef, who founded the well-known workshop in Brussels in the late 1980s, appeared on the world market quite early (the first cigarette manufacturers in Belgium were foreigners or Belgians who previously had nothing to do with the tobacco industry)

Józef’s son – Ernest Leon Sadzawka was a hero of the First World War. He began his military service on October 12, 1914 as a volunteer and fought in subsequent campaigns until the end of the war. He went down in the history of the Belgian military as an exemplary and brave adjutant, commander of the platoon of the 1st Infantry Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division, which at night from June 30 to July 1, 1918 carried out a heroic assault on an enemy post near Merkem at the Londen intersection (the Yser front) . For special merits on the battlefield, Ernest Leon received 9 decorations, including the Order of the Crown, Order of Leopold, War Cross, Victory Medal, Volunteer-Veteran Medal and a Medal Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of Belgium. Although he was seriously wounded twice during te war (August 27, 1916 and July 1, 1918; amputation of the left thumb and deep wound of the left thigh due to a fracture caused by a projectile), it was only in February 1919 that Ernest Leon asked the government to grant leave, for which he was prompted by the difficult material and health situation of his father Józef, who during the war refused to work for the enemy, ceasing operations in his tobacco factory.

Thanks to Ernest Leon, Józef and Maria received Belgian identity cards in 1920, becoming citizens of the country.

Ernest Sadzawka also went down in the history of the oldest sailing club in Belgium. The Belgian press of 1914, in both French and Flemish, has repeatedly reported on Ernest’s participation and successes in the international regattas at Ostend and Liège. In 1925, Ernest became the president of the prestigious Royal Sailing Club in Brussels. He performed this function for 35 years.

On July 13, 1920, Józef Sadzawka sold the company. According to Maria Ungermann’s correspondence to children written at the Vichy Hotel in Nice in early 1925, he died of complications caused by bronchitis. He was buried in the Laeken cemetery. His descendants today live in Belgium, France and Chile.