August 2, 2022 marks the 79th anniversary of the outbreak of the uprising in Treblinka.

Marian Płatkiewicz recalled:

“People from Płock were a pillar of the uprising. Motek Perelgryc, citizen of Płock, a bicycle mechanic. He worked in Treblinka as a tinsmith and repaired bicycles. He and his friends Łyk from Nowy Dwór and Budnik with his brother forged the key to a German weapon warehouse, they made an imprint of the key using a piece of bread. Treblinka counted nearly a thousand prisoners, and there was no one to voluntarily enter the weapons warehouse to hand over the weapons. Only Chaskiel Rozenberg and his son Szmul Rozenberg volunteered. They were let into the arsenal with weapons and they issued German automats and grenades to the insurgents through the bars. Chaskiel Rozenberg was the commander of his timber group, and in the underground he was one of the organizers of the uprising in Treblinka. He was killed during the fights. His son, Szmulek, died in the forest during the siege conducted by the Germans from outside the camp, near Treblinka. The Rozenbergs were native Płock residents. In the group of fitters, the commander was a small guy, Rudek Lubraniecki. Lubraniecki, known in Treblinka as “Little Rudek”, died during the fights at his garage in the tunnel. Rudek and the Czech Rudolf made a great panic at the SS men, blowing up a tanker full of gasoline and the oil reserves they had in Treblinka. Ber Gutman, a carpenter from Płock, worked with me in the “Kartoffelkommando”. We demolished the German “Verwaltung” during the uprising. Kryszek, a young boy from Płock, was assigned to set fire to the clothes left behind by our brothers and sisters in Treblinka. He was killed in the camp during the fights”.

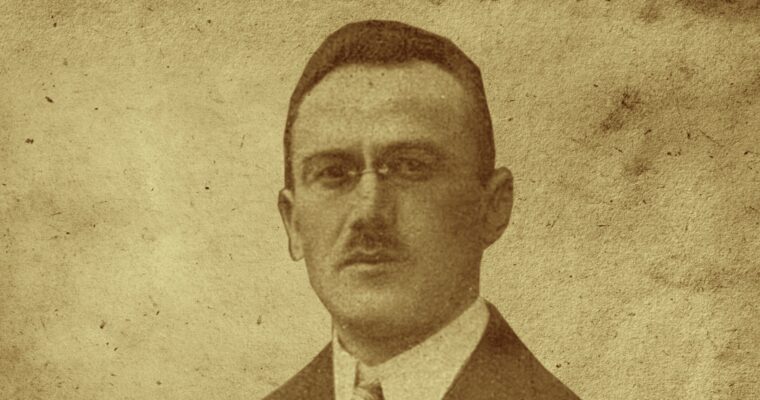

In the photo, from left to right: Motek Perelgryc, Marian Płatkiewicz and Rudek Lubraniecki.

May their memory be a blessing!

More information on the history of the Treblinka Uprising: https://polin.pl/en/the-treblinka-uprising