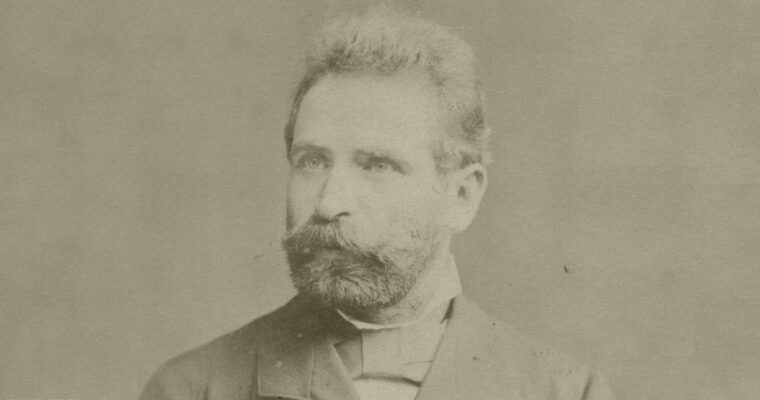

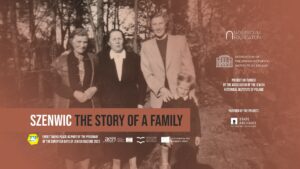

In 1832 in Płock, in the family of doctor Filip Lubelski and Wilhelmina née Frankenstein, Wilhelm Szymon Lubelski was born – a future psychiatrist, also a social activist, a favorite of Warsaw residents, appreciated for his comprehensive knowledge, sense of humor and erudition.

Wilhelm graduated from the middle school in Piotrków Trybunalski, then he studied medicine in Dorpat. He continued his education in Vienna and Paris. In 1859 he settled permanently in Warsaw. In the same year, he presented to the Medical Council of the Kingdom of Poland the dissertation On facial pain (neuralgia faciei v. Prosopalgia Fothergilli), for which he was awarded the title of doctor of medicine. In 1861, he took over the ward for epileptic women at the Infant Jesus Hospital, and in 1867, the ward for mentally ill women. He was a member of the Warsaw Medical Society (for several years he was a librarian). In 1864, together with a group of eight psychiatrists, he established a department of mental, nervous and forensic psychiatry within the Society. He was active in the construction committee of an institution for the mentally ill in Tworki near Warsaw. He was also a member of the Society of Medical Sciences and the Society of German Doctors in Paris and the Paris Society of Polish Doctors. In 1887, he co-organized a hygiene exhibition in Warsaw. Wilhelm Lubelski was a famous philanthropist, involved in the activities of the Charity Society (a doctor of shelters for the elderly and the disabled, orphans and girls).

His scientific achievements mainly include messages and reports in the field of psychiatry, neuropathology, pharmacology and hygiene, which were published in Polish, French and German journals. He also published popular science articles in non-medical journals. He was the author of the work entitled Marriage in terms of physiology and hygiene, with the addition of the dietetic notes on raising infants according to the best sources (Warsaw, 1899).

He died in 1891. He was buried in the Powązki Cemetery.

Wilhelm’s father was Dr. Filip Lubelski (1787-1879) – Haskalah activist and supporter of the assimilation of the Jewish population, he came from Zamość. He completed his medical studies in Vienna in 1811 with a doctorate in medicine and surgery. Earlier, in 1808, he joined the army of the Duchy of Warsaw, taking part in all Napoleonic campaigns. In the battle of Leipzig he was wounded with a rifle bullet in his arm. In 1813 he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Legion of Honor “for his diligence in performing his duties”. He was also awarded the Order of Virtuti Militari and the Medal of St. Helen. He was associated with Płock from around 1815. He ran a medical practice here, and in 1831 he founded a hospital for sick and wounded soldiers in our town. After the outbreak of the November Uprising, he volunteered for the army. He was a staff doctor in the Polish army. After the fall of the uprising, he returned to medical practice, which he conducted in Płock until 1840. Then he moved to Warsaw, where he worked as a doctor in the 1850s.

He died on February 5, 1879. He was buried at the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street.